|

|

|

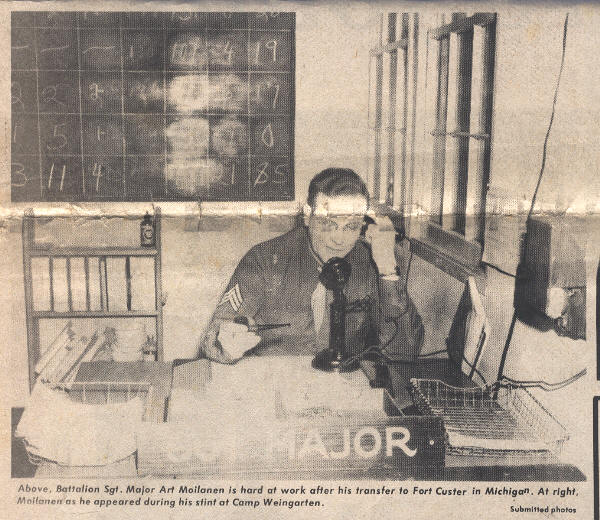

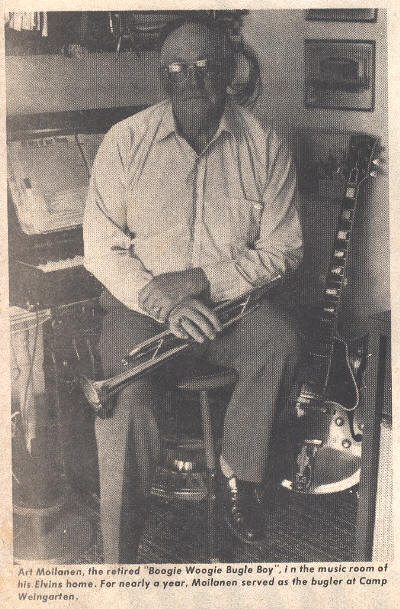

| "Some day, I'm going to kill the bugler, Some day, I'm going to shoot him dead..." Suffice it to say that Irving Berlin song probably was not Art Moilanen's favorite tune. For nearly a year, Moilanen was a bugler and the musical director at Camp Weingarten, a prisoner-of-war camp for Italian soldiers captured by U.S. troops. "For all these years, I would never say anything about my time in the service," he said. "I always felt all those boys who went over there in the action, they're the ones to be appreciated. But now, the years go by, and I think about the prison camp, and I think there's a story to tell." And there is. Moilanen and the rest of the 554th Military Police Escort Company arrived at Camp Weingarten in September 1943, and left in March 1944. "When we first got there, they wanted to know if there were any buglers," Moilanen recalled. "Well, I was an old trumpet player, and I figured I could do it. And I figured by being the bugler, I wouldn't have to work so many guard details in the tower. So I volunteered." But bugling all day wasn't quite as exciting as he'd thought it would be. "I got so bored, I would ask to go up in the tower and guard the prisoners," he recalled. There were 12 towers surrounding the fence, each manned by three guards with Thompson sub machine guns, he said. Each tower also housed a .50-caliber machine gun "just in case anything would happen." The only problem Moilanen recalled was when news of the assassinations of Benito Mussolini and his mistress reached the POWs. "I noticed these POWs come up to the gate all dressed up in their uniforms -- they had the prettiest uniforms, very colorful and real spit-polish," he said. "They came up to the gate and started to demonstrate, and I couldn't figure out why. I didn't know Mussolini was dead. "They started to bump up against the gate, which didn't have any big lock or anything. Not knowing what to do, I called the guardhouse, and the sergeant of the guard said, 'Haven't you heard?' and he told me. "Then he said, 'You go to the big window and open it and point that .50-caliber at them, and they'll just calm right down.' And they did," he said. "I often wonder if something would have happened what I would have done," he continued. "I don't think I could have fired on them. But that seemed like it cooled them down. And that was the only time I felt like there was ever in the least bit of danger." For the most part, life at Camp Weingarten was peaceful. Some 2,500 POWs were housed there, and no escape attempts were recorded. Another part of Moilanen's duties was training some of the others buglers. "I volunteered, and came to find out the other companies didn't have buglers, and they wanted to know if I wanted to instruct people to become buglers," he said. In his first class were "12 or 15" volunteers. Training went pretty well, Moilanen recalled. "It wasn't very long before we were playing those horns, and it must have sounded pretty sour, because we were told to get out into the woods or out into Weingarten and to get away from the camp," he said. "The best part of being a bugler was the cooks would wake up -- they get up at 3 -- and then they wake the bugler up," Moilanen said. "I would wake up and get next to the mess hall and then I'd play." The men would come out for Reveille, he continued, and as they lined up, "I'd hand the trumpet to one of the sergeants who was cooking and I'd be first in line." It wasn't just "Reveille" that the buglers played every day. The other calls in their repertoire included "First Call," "Overcoats" and "Fatigues" -- "I guess they thought we were a bunch of dummies or something and didn't know when to wear our Class A uniforms," Moilanen said -- "Fire" "To the Colors" and, of course, "Taps." "Those bugle calls are hard to play," he said. "You had to be a pretty fair trumpeter." Moilanen continued, "At 9:30 every night, I would play 'Lights Out,' and I'd play that call, and I could just wait a few minutes and the POWs would answer it. Sometimes on those cold nights, it was kind of mournful." He directed a 14-member orchestra, made up of seven Americans and seven POWs. They performed at dances and for the military brass who would visit the camp. "The POWs couldn't speak too much English and I couldn't speak Italian, but music being the universal language, we managed," he said. "They were very good sight-readers," he continued. "They could take that music and look at it and just play it instantly. Those younger days, I thought I was just pretty good on that trumpet. I had this trumpet player from Rome -- Carlo, his name was -- a very fine trumpet player. "I took the first trumpet part, but I soon found out I better take second, 'cause Carlo was just flat good." Off-duty, their music selection changed. "We played the music of the 40s," Moilanen said. "Glen Miller, Tommy Dorsey, all of them." "I'll Be Seeing You," "The White Cliffs of Dover," "Marie" -- those were the melodies he and his ensemble played, along with songs like "Sorrento" and "I'm Getting Sentimental Over You." In June 1944, Moilanen's company was pulled out of Camp Weingarten. "I didn't know it at that time, but we were being assigned for the D-Day push, June 6, 1944," he recalled. But Moilanen was not to join them. A leg injury suffered in a training exercise and a last-minute bout with appendicitis held him back. Instead, he was sent to a base in Michigan, where he reached the rank of Battalion Sergeant Major. Off-duty, he played in clubs around the area, as he continued to do when he left the service, earning the billing, "The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B," of course. Moilanen is retired from his job as crane operator now. He and his wife, Leanna, live outside Elvins. They met in Flat River when he went into town on a pass. She was working as a soda jerk at Wood's Drug Store. "That was one of those rare weekends we got passes into town," he grinned.

|

||

| "For 20 years, I wondered about those boys in that company, 'cause I knew they all went into Normandy, and I heard nothing for 20 years. I presumed them all dead, and I felt kind of guilty about it, 'cause I should have been there with them. Then one day I was in Ste. Genevieve and I thought about a friend of mine. He had married this girl who was from there, and I looked them up, and there they were," he said. "He was living in Ste. Genevieve all these 20 years, and I hadn't known it. We had quite a discussion. He said there wasn't a one of them got killed. The day after it was all over with, one of the guys actually shot himself in the foot while he was cleaning his gun." Moilanen has finally told his story about his part in the war, and he enjoys the chance to reminisce. But he carries his reminiscences no farther than the stories he tells about Camp Weingarten. "When I go by there, I never stop," he said. "I've only been there once, when we came back here to live, and they hadn't torn too much of it down. I drove in there, and it seemed like I had died and come back. It was another time, another place. "I went back there, and I got the worst feeling that I dreamt all of this." Published by THE DAILY JOURNAL, Flat River, St. Francois Co. MO, Fri. April 29, 1988 in a supplement "Back in the 40's When You and I Were Young." |

||