![]()

|

|

|

![]()

Rangers - Father, son serve with honor

Hurley

makes it clear he joined the U.S. Army in 1937 out of economic necessity, that being to

escape the grips of The Great Depression. What

lie ahead for him and millions of others was beyond his imagination.

It

is clear that Hurley is reluctant to talk bout his wartime experiences.

"So

many buddies got killed," Hurley said, looking down.

"Some I had been with about five years.

It is hard to look back."

With

the hardships and a physical injury that was near fatal, Hurley's greatest grief comes not

from his own wartime encounters but the loss of his son, Sgt. Maj. Patrick R. Hurley, in

Operation Desert Storm.

Like

his father when he scaled the cliffs at Normandy, Patrick Hurley was an Airborne Ranger

and when he was fatally injured in a helicopter crash he was a member of the Special

Forces elite Delta Force. He was on a rescue

mission behind the lines, an operation so confidential that the government still has not

released all of the details.

Robert

Hurley and his wife, Mabel, as well as other family members, were honored guests last year

when a lake at Fort Bragg, S.C. and a training hill at Fort Benning, Ga., were named in

honor of Patrick Hurley.

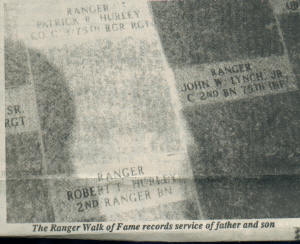

The

senior Hurley, once a Ranger in World War II, was again named an "honorary

Ranger" by his son's unit and a more touching honor was bestowed when the names of

Robert and Patrick Hurley were placed together on the "Ranger Walk of Fame" at

Fort Benning.

|

Tears

come to the eyes of both Mr. and Mrs. Hurley when they speak of their son. Their home is filled with photographs and other

momentos related to their hero son.

The

Hurleys built the house they live in more than four decades ago, but sold it when they

moved to Illinois. After Patrick's death, they

moved back to Missouri and were fortunate enough to be able to repurchase the home in

which he and their other children had grown up.

The

house sits on a hill overlooking Big River, and so fittingly in front a U.S. flag flies

briskly in the wind.

Robert

Hurley recalls the African campaign as the easiest part of the war. There the troops his unit faced were mostly

Italians who had lost the will to fight.

"They

wanted to surrender," Hurley recalls, "but they had German officers and NCOs who

would not let them give up."

It

was the assigned task of the 2nd Ranger Battalion to take the big German guns atop the

cliffs at Normandy, Hurley remembers. They had

to scale the cliffs and it was virtually a suicide mission for those Rangers.

"We

lost 136 men," Hurley said with both sadness and anger in his voice. "It was uncalled for."

Hurley

explained his bitterness. The artillery

emplacements were there, but there were no big guns in them.

But the Germans defended the positions with great vigor, using machine guns

to mow down the climbing Armericans.

The

toll would have been much greater, Hurley said, except for the fact that he and some other

Rangers saw what was happening and went to the flanks.

They managed to get around and take out the machine gun emplacements so that

those still on the cliffs could reach the summit.

While

the memories of his days with the Rangers a half-century ago still leave him bitter,

Hurley has a new respect and love for the Army.

"They

are the greatest," both Hurley and his wife said, referring to the way they have been

treated since the death of their son.

Patrick's

nearly 19 years in the Army has obviously renewed the couple's admiration for the

military. He went into Iran when Americans

were being held hostage, was in an advance force that went into Panama and was among the

first in during the Persian War.

After

Robert Hurley joined up with the 30th Infantry, it battled its way across France, Belgium

and northern Germany. He was in the Battle of

St. Lo where he recalled they put out smoke to guide Allied bombers but the wind blew the

smoke back over their position and it was the Americans who took the brunt of the bombing.

Hurley's

memories of the Battle of the Bulge are also none too pleasant.

"It

was bad because of the fog," he recalls. "The planes couldn't see us."

The

weather kept Allied aircraft from dropping in supplies to their troops as well as

prevented them from bombing the deadly Tiger tanks of the Germans. "After the weather cleared up the planes got

rid of the tanks."

Another

memory he shared, though he will talk in little detail, ws that during the Battle of the

Bulge "it was cold as the Dickens."

With

the war over in Europe, Hurley got a break. He

got to spend about two weeks leave and then was off to the Pacific and the Philippine

Islands.

Joining

up the with the 11th Airborne, Hurley jumped into northern Luzon where the unit had a

mission of rescuing American prisoners of war who had been part of the Bataan Death March. It was in that jump that he was nearly killed.

"My

chute split and I landed on my head and shoulders," Hurley said. "I don't know how I got to the hospital. I don't remember anything about it but I wound up

in the hospital at Manila."

Hurley

suffered a hemorrhage of the brain. After 30

days hospitalized at Manila, he was transferred to a hospital in Battle Creek, Mich.

That

was to be the end of Hurley's military career, one that had taken him through bitter

conflict on two continents and in the South Pacific.

The information on this site is provided free for the purpose of researching your genealogy. This material may be freely used by non-commercial entities, for your own research. The information contained in this site may not be copied to any other site without written "snail-mail" permission. If you wish to have a copy of a donor's material, you must have their permission. All information found on these pages is under copyright of Oklahoma Cemeteries. This is to protect any and all information donated. The original submitter or source of the information will retain their copyright. Unless otherwise stated, any donated material is given to MOGenWeb to make it available online.