HISTORY OF SLAVES By Roger W. Forsythe/Daily Journal Staff Writer |

|

HISTORY OF SLAVES By Roger W. Forsythe/Daily Journal Staff Writer |

|

Like pick locks of the past, a forgotten heritage scarcely conceived exists to this day in the spidery script of yellowing manuscripts and the crumbling bricks of modern reconstruction.

Such it is with the history of slavery in St. Francois County.

While extensive research has shown that at least 10 skirmishes and engagements took place within the county's boundary during the Civil War -- with the two biggest battles having been fought at Big River Mills, near Desloge -- scant evidence has been found on what has been described as "that peculiar institution"...until now.

The enslavement of Native American Indians and transplanted African-Americans was first introduced in this area in 1720, when both groups were forced to work in the nearby lead mines. In 1834, 12 years after St. Francois County's incorporation, Indian slavery was declared illegal.

According to figures released as part of the 1850 Census, the county at that time had a white population of 7,549 residents. Another 889 were slaves and 91 were slaves that had been freed. Ten years later, these same numbers had changed to 9,292 whites, 877 slaves, and 80 free slaves.

With the noted exception of St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve Counties, St. Francois had, in fact, more freed slaves than any other of Missouri's then-84 counties.

As is true with any historical research, a little detective work only leads to more

questions and more avenues of pursuit. Jeannie Roberts of Farmington, for example,

reported Tuesday afternoon that an underground tunnel is believed to have run from her

home's foundation to the "Cayce House," located across the street at 503 West

Columbia Street.

|

"My son thinks he's found where the entrance was, but I've never seen it," she said. "We have a carriage house in back and, as far as I know, it was never used as slave quarters. It was built in the early 1860's."

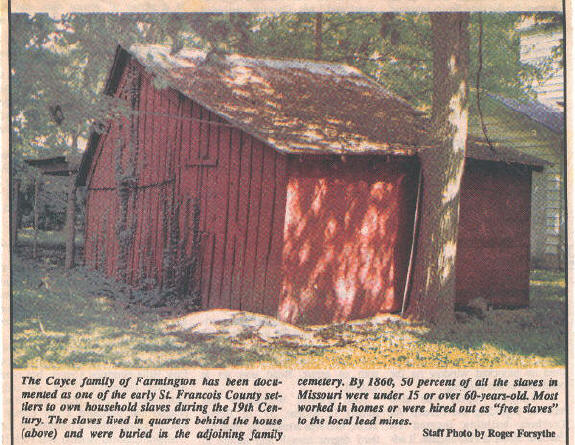

According to information compiled as part of a self-guided walking tour published by the First State Bank and City of Farmington, the Cayce family "owned slaves who lived in quarters behind the house until the end of the Civil War." That site is believed to have since been rebuilt as a shed.

Records housed in the genealogy room at the Farmington Public Library also show that 19

markers have been indentified in the Old Cayce Cemetery, situated beside the "Cayce

House" on adjoining property. The oldest record dates back to Pleasant Cayce, who was

born in 1767 and died on Nov. 20, 1811.

Steve Grider, St. Francois County Recorder of Deeds |

For the past several years, members of the St. Francois County Historical Society have met each Tuesday morning at the county courthouse to preserve much information which would have been lost otherwise. And, of course, probate records, marriage licenses and even receipts for the sale of property have documented slavery's existence.

Despite all that has survived, an unknown wealth of information has either passed from memory or been tinged with the homespun thrill of legend.

For example, one resident has indicated that a six-foot-square monument is believed to have stood, and may still stand, just off the Old Fredericktown Road on what is now private property. This mass grave marker was built by early Spanish settlers making use of slave labor.."so the story goes."

That a number of homes throughout the county housed separate slave quarters or a cellar in which slaves may have been kept should come as no surprise -- especially when given an overall understanding of a period in which liberty could be bought and sold, for a price, on the auction block.

In her presentation early this month to the Southeast Missouri Civil War Round Table at Ironton, Suzanne Ninichuck cited the accounts of the Missouri General Assembly, Earl J. Nelson's 1932 thesis and Peter Parrish's research in laying the groundwork for how slavery came to exist in this part of the state.

Within a century after its introduction, slavery was sectional and divided into "task" and "gang" systems of management. State laws required slave owners provide shelter, food, clothing and medicine -- and outlined regulations to prevent mistreatment.

"It was an unusually secure environment," Ms. Ninichuck began. "They were given holidays off, passes, money, garden plots -- a lot of perks and incentives. It wasn't all in one direction. It was a two-way game, and it was very much a social thing.

"To be a decent family, you had to have a household slave. In Missouri, 'gang' slavery (in the fields) was not economically feasible. And the slaves heard a lot of horror stories about being sold 'down the river.' They feared that worse than whippings because they knew they didn't have it so hard up here."

Even so, slaves were -- to put it bluntly -- property. The Bill of Rights offered neither solace nor protection. While state and county laws dictated what they could and -- more often than not, couldn't -- do, these were invariably supplemented with the owner's law, which reigned supreme.

Slaves were often "hired out" when they were not needed at home or when the hemp growing season was over. Less than six generations ago, hemp (marijuana) was Missouri's number one cash crop, closely followed by tobacco and corn. Now illegal, this contraband was used for rope and bagging cotton until metal hoops were invented in 1858.

Some slaves were allowed to enter into employment contracts, earning enough money to buy themselves (and their families) out of bondage. Directly linked with the going market price for cotton, slave prices held steady between $500 and $1,000 up until 1864.

Because owners were held responsible for the actions of these hired-out "free slaves," they had to guarantee their mental stability, honesty and ability to live independently.

But even this action sparked racial turmoil. In the St. Francois County lead mines, the most dangerous jobs were doled out to white immigrant settlers because compensation would be due the owner should a "free slave" be injured or killed.

Of course, such disparity between races -- almost a form of reverse discrimination -- led to considerable dissension among the growing population of European immigrants, who viewed free blacks as an economic threat and the chief competition for low-paying jobs. Between 1825-60, one non-profit group went so far as to raise enough money to send 35 blacks back to Africa.

"Missouri was a difficult place for the Emancipation (Proclamation)," Ms. Ninichuck said. "Because Missouri and Kentucky held with the Union, the Emancipation was worded so that it would say 'or persons in rebellion.' But they were still selling slaves in St. Louis until the end of the war. It was just a propaganda ploy."

In 1847, just four years after free blacks were barred from moving into the State of Missouri, it became illegal to teach slaves how to read and write. By that time, however, some free blacks were already wealthy enough to purchase their own slaves and property. One enterprising minister established "The Freedom School" for blacks on a riverboat in the middle of the Mississippi River.

Ms. Ninichuck continued: "Another thing to remember is that everybody from all over the country was coming here. It was not Missouri fighting against itself. In 1840, only 44 percent of the population had been here for 10 years. And in 1850, 60 percent of the population were outsiders and 30 percent were local."

Statistics show that Missouri's 1850 population stood at 265,304 native Missourians, 249,223 western-bound Americans (primarily those from Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina), and 76,570 foreign immigrants (primarily Irish and German). Within 10 years, these numbers had shot up to 475,246 native Missourians, 431,294 migrating Americans, and 160,541 immigrants.

"Between 1850-60, the majority of Missourians were from Kentucky, and they brought their slaves with them when they moved. As the number of Kentuckians declined, so did the number of slaves. And at about the same time, the number of foreigners went up.

"A lot of these new immigrants were violently opposed to slavery because it reminded them of the aristocracy and the serfs they had left behind in Europe. Most all the slaves were along the Missouri River, with some down in the Bootheel. In fact, 86 percent of the state's entire population lived along the Mississippi River."

With Missouri's first, furtive steps on freedom's road, "co-habitating" free blacks were allowed to legally marry -- and their "reputed" children made legitimate -- after Feb. 15, 1865. Many took the surnames of their owners.

Finally, while it is believed to have been active in St. Francois County, Ms. Ninichuck stated that in all her research she has found "not a mention" of the Underground Railroad.

The following slave narratives which relate to St. Francois County, Missouri, were found in the free data base at Ancestry.com . In 1929, an effort began at Fisk University in Tennessee and Southern University in Louisiana to document the life stories of former slaves. Kentucky State College continued the work in 1934 and from 1936-1939, the Federal Writer's Project (a federal work project that was a part of The New Deal) launched a coordinated national effort to collect narratives from former slaves. This following interviews provide a poignant picture of what it was to live as a slave in the area of St. Francois County, Missouri.