In the year 1843 a St. Louis newspaper

published the following description of Iron Mountain:

| "It is about a mile broad at the base, 400 feet high and

three miles long; and has the appearance of being composed of masses of iron ore. It is

literally a mountain of ore so pure that it yields from 70 to 80 per cent under the

ordinary process of converting it into malleable iron. At the base the ore lies in pieces

from a pound weight upward, which increases in size as you ascend, until they assume the

appearance of huge rocks, which would remind the beholder of those "fragments of an

earlier world" of which the Titians made use. Six miles southeast in another mountain

called Pilot Knob, composed of a macaceous oxide of iron lying in huge masses. This ore

will yield about 80 per cent of metal." |

This huge mountain of iron was the subject of conversation

throughout the nation. Immigrants from the

European countries heard of it immediately upon their arrival in New York and as a result,

many of them came to Missouri and settled in the vicinity of Iron Mountain. For a time the people of the Atlantic Sea Board

considered it a fable. They referred to it as

a mineralogical joke. It is said that at the

White House dinner, the president of the United States, with a skeptical smile, said to

the wife of a senator from Missouri, “Mrs. Linn, I hear you have, in your state,

iron ore so pure that it does not have to be smelted; that you forge directly from the

ore.” Mrs. Linn informed him that his

information was correct and when she returned to Missouri, she sent to the president, a

knife made by a Missouri blacksmith from a chunk of ore.

Much missionary effort was required to impress the people of the east about the

truth of the mineral riches of Missouri. Senator

Linn obtained from the much ridiculed Iron Mountain a lump of ore weighing two tons and

sent it to Paris for examination by men of science. These

experts gave formal judgment that this Missouri ore was the best of iron, and for many

purposes, far superior to any they had ever seen. They

were so much interested that they made a set of ornaments from this ore and sent it to the

wife of the senator. For many months Mrs. Linn

wore her Paris-made jewelry of iron for the benefit of Washington doubters.

Examining the

history of this Iron Mountain, we find that during the latter part of the 18th

century, the Spanish government gave this mountain to Joseph Pratte. The grant covered a

tract five miles square, with the mountain located about the center and was referred to as

“a concession or order of survey made by Zenon Trudeau as lieutenant-governor of the

western part of Illinois, in favor of James Pratte and dated October 17, 1797, for 20,000

arpens, on the waters of the river, St. Francois.”

We are told that Pratte was a man of great influence in southeast Missouri,

or as it was then known, Upper Louisiana. He

had made himself especially useful to the government in adjusting Indian

troubles—there was no man in all those parts who could go out and pacify the Redskins

as Pratte could – and he was frequently in demand to act as an arbitrator in the

differences which arose between the settlers and the Indians. One of the largest of the Indian towns in that part

of the country was at the base of Iron Mountain, and it is probable that Pratte gained his

knowledge of the mountain from the visits he made to this Indian town on his peace

errands. However, when the governor of Upper

Louisiana suggested to Mr. Pratte that his services entitled him to recognition and asked

him what he should recommend to the government as a suitable honorarium, the peacemaker

said he would take this mountain. Pratte died

and the grant was ultimately confirmed to Joseph Pratte and his legal representatives.

The records of

the Missouri Board of land commissioners show that on June 25, 1833, the board recommended

that the grand or claim ought to be confirmed to Joseph Pratte or to his legal

representatives; Francis Valle, Charles C. Valle, Robert T. Brown, and Catherine Brown

(his wife), Walter Wilkerson, and Emily Wilderson, George Bullet, and Celest M. Allen. The land records then disclose that the title

remained in the Pratte heirs for several years until John Livingston van Doren of Washington

county, Missouri, became interested in the property and began to acquire the interests of

the various heirs. In their conveyance the

property was referred to and known as the Iron Mountain tract. In December 1836, the Missouri Iron Company was

incorporated by a special act of the Missouri legislature, which was the statutory method

of forming corporations in those days, and van Doren conveyed the tract to said company on

March 9, 1837. In this conveyance, the tract

is referred to as Iron Mountain, situated on the head waters of the St. Francis River and

adjoining Missouri City, containing about 4500 acres and being a part of the concession of

20,000 arpens of land by the Spanish government to Joseph Pratte. It is interesting to note also, that in this

conveyance, the sale or gift of spititous or intoxicating liquors, gambling, lottery or

houses of ill fame, were prohibited on said lands with a provision that said restrictions

should be incorporated in future deeds. The

conveyance contains a further provision that “the party of the second part agrees to

give Missouri City University, 1/10 of all funds arising from the sale of native and

unwrought iron ore of the Iron Mountain or any of the ore beds or mines owned by said

Missouri Iron Company.” The consideration for the conveyance was 49,945 shares of

stock of the Missouri Iron Company. This deed

also conveyed “a tract in Madison county, Missouri; including a mountain of ore,

which mountain is known by the name of Pilot Knob—and the president and board of

directors of said Missouri Iron Company—bind themselves to construct a railroad from

the Iron Mountain to Iron Mountain City on the Mississippi River or to such other point

hereafter to be selected by said J.L. van Doren on said river within five years from the

date hereof.”

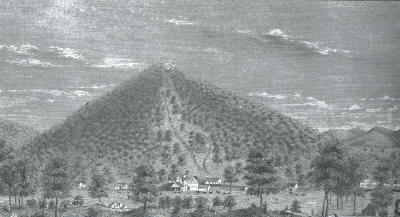

Pilot Knob Mountain, Circa 1855

|

Here is proof of record of the

often repeated tale that the Iron Mountain mine was responsible for the construction of

one of the major railroad systems of our country. Originally

it was the St. Louis

and Iron Mountain Railroad Company, as we will note from a later reference in this

memorandum.

One of the most interesting conveyances

of record in the chain of title to the Joseph Pratte Survey is a conveyance in 1838 in

which the grantee, Missouri Iron Company, agreed to “present by a good and sufficient

warranty deed, 300 acres of farming land lying north and northwest of Missouri City and

not more than a half mile from the present north line of said plat and also all the

building lots as contained in Block 20, 35, 26, 44, 54, 63, 70, 80, and 87, and lots 1, 2,

3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 in Block 45, and lots 4, 5, 6, and 7 in Block 55, to the president

and trustees of the Missouri City University; also all the lots in Block 52 to the said

president and trustees of the Missouri City University for a young ladies institute; and

also lots 4, 5, 6, and 7 in block 94 to trustees of the Trinity church; and lots 1, 4, 5,

6, and 7 in Block to St. Paul’s Church, said churches to be the Calvinistic

Protestant Episcopal church; also lots 7, 5, 6, and 1 in Bock 28, and lots 4, 5, 6, and 7

in Block 43 to the Presbyterian church of the United States of America; also lots 4, 5, 6,

and 7 in Block 74 to the Methodist Episcopal church: also lots 4, 5, 6, and 7 in Block 57 and lots 4, 5, 6, and 7 in Block

123, to the open Communion Calvinistic Baptist Church; all the block north of Block 1 to

the trustees of an orphan’s asylum; all of the block north of Block 24 to the

trustees of a lunatic asylum; all the block north of Block 42 to the trustees of a city

hospital; all the block north of Block 61 to the trustees of a deaf and dumb asylum and

all the block north of Block 78 to the trustees of an asylum for the blind; also a lot of

50 acres of land to the trustees of a house of refuge for juvenile delinquents, to be

situated not less than 1 � miles northeast of the city plat on the present Iron Mountain

and Farmington road; also the whole of the City Hall Park to the corporation of Missouri

City for a city hall; also to appropriate lots 3, 4, 5,

6, 7, and 8 in Block 101, for

two hotels to any individual who should obligate themselves to erect them subject to the

approval of the Board of Directors of the Missouri Iron Company; also the eastern half of

Block 136 and the northern half of Block 68 to the corporation of the city for two market

houses; also all of Block 130 to the trustees of a widows’ asylum; also Block 19 to

the trustees of a city lyceum; also lots (any eight) to the trustees of public schools;

also 25 acres of good farming land for a city flower garden to be situated not more than

one mile from the city plat, to the trustees of a city horticultural society; and 30 acres

for a city burying ground, not to be more than two miles from the city plat, to the

trustees of said burying ground, said ground to be laid out on the plan of Mount Auburn

Cemetery near Boston.”

“The party

of the second part further covenants and agrees that 11 of the buildings and other

improvements in said Missouri City shall be required to be situated and erected not less

than 12 feet from the front line of said lots and also that all lots sold be required to

be improved within five years from the date of sale, except lots used for ornamental lots

or ground adjoining other improved lots, and that all such buildings and improvements

shall be in strict conformity to an exterior plan designed and previously determined upon

by the Missouri Iron Company for the particular block in which said buildings are to be

erected, thereby giving uniformity to each city Block; also lots 4, 45, 56, and 7 in Block

67 and lots 4, 5, 6, and 7 in Block 52 to the catholic Church; all the foregoing lots for

the building of churches are to be deeded to the respective denominations as soon as

regular congregations obligate themselves to erect upon their respective building lots,

frame, stone, or brick houses of worship, not less than 50 x 80 feet on the ground.”

A reading of the

contents of this conveyance convinces one that the interested parties were sure that they

owned an iron mine which would support the metropolis of the Middle West for many years to

come, and certainly it cannot be said they were not men of vision who believed in making

due preparation for future developments. Unfortunately, Missouri City did not develop in

accordance with their dreams.

It is apparent

from the land records that about this time the mining industry at Iron Mountain began to

experience financial difficulties, and the records show that in October 1841, the property

was sold at public sale by the sheriff of Washington County, Missouri, under execution for

debt; and the purchaser was Conrad C. Zeigler. The

property was also sold in November 1841, at public sale by the Sheriff of St. Francois

County, Missouri (the sheriff being Milton

P. Cayce, one of the early residents of St. Francois County and father of M. P. Cayce

who resides in Farmington now); and the purchaser at this sale was also Conrad C. Zeigler,

who was again the purchaser at a public sale by the sheriff of Washington County,

Missouri, under execution for debt in February 1842.

In 1843 Conrad C.

Zeigler and James Harrison, having purchased the equity of the former owners, obtained a

charter for the American Iron Mountain Company which was incorporated by the Missouri

legislature. In 1845 Zeigler and Harrison

conveyed the interests which they had acquired and vested title to the property in the

American Iron Mountain Company.

It was in 1855 that the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad Company was constructed and a

right of way deed was recorded by which the American Iron Mountain Company conveyed a

right of way over its lands for railroad purposes. Until

1871 the terminus of said railroad was at Pilot Knob, Missouri. Prior to this time there was no railroad, and the

only outlet to market was by wagon eastward forty miles or so to the river. About midway between Iron Mountain and the river,

furnaces were built for the reduction of the ore, and these were operated for many years

under the name of Valley Forge. The forge,

however, was a part of the Iron Mountain enterprise; the ore was laid upon wagons, hauled

to the forges, there converted into blooms and then transported to the river to be

distributed throughout the Mississippi Valley. Then,

to expediate the business, a plank road was built and for many years the traveler

encountered at two or three places on the “pike”, as it was called, the long bar

which was lifted only when the regulation toll was paid.

These toll gates were in existence until the early part of the 20th

century and were the last relics of the toll gate system in Missouri. The forge was located near Farmington for the

reason wood was plentiful in the vicinity. Vast

quantities of charcoal were used in the furnaces. To

keep up the supply, the company bought tracts of land solely to acquire the timber on

them. This accounted for the possession at one

time of 32,000 acres, nearly double the amount conveyed by the Pratte grant, which with

its 20,000 arpens (approximately 17,000 acres) lay in one body. The other tracts were scattered over a stretch of

country 30 miles long and dozen miles wide.

Wagoning iron

ore and blooms proved too slow and too costly, but even with that method of transportation

the American Iron Mountain Company made such a showing of enterprise that capital was

tempted to result. Its construction was

prompted and encouraged by the prospect of ore and iron shipments.

It is a matter

of record that early operations were primitive. The

ore was picked from the crest of the mountain in chunks, trundled down the mountainside on

tramways and laid on the cars ready for shipment. Pick

and shovel dislodged the masses. Gravity

furnished the power, for the loaded car getting down, pulled the empty one up. That was picking up dollars. One workman was good for six or eight tons a day. Ore was worth nine and ten dollars a ton, and 100

cars a day left the mountain for the furnaces. There

were periods when the shipments went over 1,000 tons a day, and every on meant a

five-dollar bill to the stockholders. A net

income of $5,000 a day, it meant.

The cap of the mountain

was taken off and then the core was excavated. The

visitor stood on what looked like the edge of a crater and gazed down on the network of

tramways and inclines and saw the stalwart miners following the veins downward so far away

they looked like small boys. One of those

veins was twenty-five feet thick and pure ore—so pure that is seemed probably it was

the vein through which the molted ore found its way upward to the summit of the mountain. This vein lay perpendicular. It was, to all appearances, the mother vein of Iron

Mountain. In the other veins and deposits

there was more or less dirt or rock mixed with the ore, and the product from them was put

through an elaborate process before it was ready to ship.

First, it was hauled out, heaped up and hydraulicked. Up the valley there was a massive stone dam which

caught the waters of Indian Creek and formed a lake large enough to furnish good fishing

the year round and a big crop of ice in winter. The

water from this lake was pumped to the top of the neighboring mountain and there kept in a

concrete tank, which held 700,000 gallons. The

rocky summit made excavation impossible, and the concrete walls were build fourteen feet

above the surface. From this tank, pipes led

down the mountainside, across the valley and to all parts of Iron Mountain. This water, with a pressure of from twenty-five to

forty pounds, was turned on the ore piles until all the dirt that could be washed away was

carried off. Then the ore went to the

separator to be rolled, rattled, and shaken over screens and jigs. At every stage in this process some ore, being

heavier than the rock, dropped out until finally the tailings contained only a small per

cent of mineral. The product of the mine lost

fifteen per cent of its weight in the washing process and twenty per cent in the

separator, but the process paid. One man with

his stationary hose could hydraulic a thousand tons a week, and the separator did its work

as rapidly as the carts could unload into the mouth of the revolving funnel. Iron manufacturers like their ore cleaned. It saved the cost of reducing clay and rock along

with the metal. Some of the ore came from the

separator in pieces that size of macadam, and some were small as grains of corn. There were five sizes, but they all were mixed

together from the market, and they graded from sixty to sixty-five per cent iron.

Iron Mountain

was one of the natural wonders of the world. For

two generations, scientific men came to see, marvel, and speculate on the origin. Every week there was at least one arrival. The hotel register read like the front part of a

college catalogue or the roll of an academy of science.

The treatment of these visitors was another of the peculiar things about the

Iron Mountain management. The latch-string was

always on the outside. Not only were the mines

open to inspection, but from the superintendent down there seemed to be a tacit

understanding that all information possible

should be cheerfully furnished.

Early Iron Mountain Mining Operation

|

Underground

mining gradually took the place of open work at Iron Mountain. For some years there was nothing to do but to pick

up the ore in chunks as it lay piled on the crest of the mountain. This formation was forty feet thick in places. When the chunks had been cleared away, then came

veins of all sizes and extending in all directions. Some

of them curved and twisted into the most fantastic forms.

Some were almost perpendicular and some were almost horizontal. Theory accounted for the layer of chunks on the

surface by the supposition that at some time there was an upheaval and the molten ore

spouted into the air to a considerable height and fell back to be broken and scattered

about over the mountain top. The same theory

supposed thyat when the upheaval came, lifting the porphyry, limestone, and sandstone, the

molten ore poured through the broken masses and filled innumerable crevices; and thus the

bewildering confusion of ore veins and deposits was accounted for.

Scientists had

to construct theories for Iron Mountain alone. Conditions

there had no parallels anywhere else. But it

must be admitted that the gentlemen were equal to the demand upon their theorizing powers. They came, wandered over the mountain, and gazed at

the formations through their spectacles. They

sat on the gallery of the comfortable Iron Mountain hotel, while the evening breezes

played, and told Superintendent Philley how it all came about. To be sure, the theories varied a great deal. One man thought the formation was aqueous; that the

upheaval took place when the mountain tops were covered with water. Another man was just as sure the molten ore spouted

up after the water receded. Mr. Pilley

listened. The professor who had spent two days

there knew ten times as much about Iron Mountain as the superintendent, who had been there

a quarter of a century did. That is, if the

hearer might judge from the emphatic assertions of one and the guarded expression of the

other. But the superintendent had learned by

long experience that nothing was certain at Iron Mountain except the existence of ore. He knew what he saw and that was enough.

After the

surface chunks were removed, the veins and deposits were followed down, some of them a

hundred feet and more. There used to be a

little mountain. It was in the nature of a

western annex, for there was a depression between the two summits. The little mountain became a great hole in the

ground. It had a thick vein, which dipped at

an angle of 38 degrees. This vein was worked

as an open cut, until all that was left of the little mountain was the hole. The vein was followed to a depth of 280 feet. For a long time the ore was hauled up to the edge

of this cavity and then run down the other side to the railroad track. This became too long a haul. A shaft was sunk at the base of the little

mountain, and ore was taken out by underground passage.

With perfect

confidence, the Missourian, before the war, spoke of the iron deposits near by as

inexhaustible. At Iron Mountain a shaft had

been sunk 144 feet. It gave fifteen feet of

clay and ore, thirty feet of white sand, thirty-three feet of blue porphyry and

fifty-three feet of pure iron ore in which they are still at work. This was at the base of the mountain. These explorations were thought to justify the

conclusion that no other country in the world of the same extent had so abundant and

accessible a supply of iron as Missouri.

But there came a

time when the ore deposits at Iron Mountain appeared to have been exhausted. Operations were suspended in the latter part of the

19th century. For a number of years

the property lay idle. It then drifted into

the hands of promoters. In 1904 it was

conveyed to James W. Darst who shortly thereafter conveyed it to William H. Smollinger. He was much interested in the breeding of find

horses. He constructed a fine race track on

the property immediately west of the Missouri-Pacific railroad right of way and for

several years he was known throughout the Mid-West where his horses won many State Fair

prizes. In 1917 he conveyed the property to

Pleasant Valley Development Company, a Kansas City outfit headed by Mr. E. E. McKee. Then about 1918, Mr. W. J. Elledge appeared on the

scene. Elledge was a mineral hound; spending

all his time on the trail of minerals and mining prospects.

He acquired title to the property and for more than two years made valiant

efforts to finance operations. He finally

conveyed the property to Earl A. Clemons, who was a Chicago man at that time interested in

a mining enterprise in Wayne county.

In May 1920, the

property was purchased by Leonard A. Busby of Chicago and he organized another Iron

Mountain Company. Mr. Busby was a highly

successful lawyer and business man in Chicago, for many years president of the Surface

Railway Lines in that city; between 1920 and 1927 he devoted much of his time and money in

an effort to revise the mining industry at Iron Mountain.

It is a matter of record that he and his business associates lost in excess

of one million dollars in cash, in their operation during the seven years mentioned; and

approximately seven hundred fifty thousand dollars of this amount was out of Busby’s

individual pocket.

In 1927, Mr.

Busby succeeded in interesting the M. A. Hanna Company of Cleveland, Ohio, and the Hanna

interests furnished funds for further exploration work.

As a result, new and additional ore bodies were discovered which had escaped

the attention of all previous owners and operators, who had been interested in the

property for more than a century. Other

difficulties remained to be surmounted, however, by way of smelting and transportation

expense and as a result, the mine has only resumed operation.

This property has had an extremely interesting history; only a brief outline has

been presented here. Iron Mountain has seen

its good days and its bad days during more than one hundred years of intermittent iron

mining operations. Under present conditions,

with the property in the hands of one of the outstanding iron mine operators in the

country and with sufficient ore in sight for many years of operation, there is no reason

to doubt the statement recently given to the press by an official of the M. A. Hanna

Company in which he predicted that “operations having been resumed, Iron Mountain

will be in operation from now on.”

The Beautiful Arcadia Valley

|

The Iron

Mountain mine is almost at the doorstep of Arcadia Valley.

While the major portion of the property is located just across the county

line geographically, Iron Mountain is a part and parcel of our community, and it is with

great pleasure and personal satisfaction that we welcome the people who are going to be

responsible for its future.

NOTE:

We're not sure of the exact date that the above article was written by Judge Edgar, but

believe that it was written sometime in the 1940's. Many thanks to

Jeanne Nassaney for transcribing the above article for us!

IRON MOUNTAIN - A BRIEF AUTHENTIC HISTORY

The iron ore found at Pilot Knob and Iron Mountain was from all

accounts the most extraordinary and immense deposit that the world ever produced. The

original height of Iron Mountain was two hundred twenty-eight feet above the valley, and

its base covered an area of five hundred acres of land; its shape was of a conical

character. Pilot Knob lying to the south, had an elevation of four hundred forty feet

above its base and covered an area of five hundred fifty-three acres. It rises like a

pyramid. Mr. Featherstonbaugh's geological report to Congress in 1836 stated, "There

was a single locality of iron offering all the resources of Sweden, and of which it was

impossible to estimate the value by any other terms than of a nation's wants." C. A.

Zietz, of New York, with large experience in iron works, in the year 1837 stated that the

iron of these mountains bear seventy per cent ore, being of the best quality.

The Iron Mountain was an original grant by the Spaniards to the Francis

Valle heirs, containing twenty four thousand acres of land which was confirmed to Joseph

Pratte by Congress July 4, 1836. Henry Pease, Livingston Van Doren and J. D. Peers

purchased the Iron Mountain property and formed a corporation of it together with Pilot

Knob, called the "Missouri Iron Company," by an act of the Missouri Legislature

of December 31, 1836, with a capital of $5,000,000. They contemplated the erection of iron

furnaces and the project of a railroad from these iron deposits to the Mississippi River.

This company did not succeed, however, and the Iron Mountain property was organized under

the style of the "American Iron Company," in the year 1845. Among the owners

were Pierre Chauteau, Felix Valle, James Harrison, C. C. Ziegler, John P. Scott, August

Belmont, Samuel Ward and Evareste Pratte. The iron deposits remained unproductive and

unworked until 1845 and the first shipment in Missouri of iron from Iron Mountain and

Pilot Knob to Ste. Genevieve over the Old Plank Road was in 1853.

A picture of life at Iron Mountain between the years 1848 and 1860 would

look something like this. There were twelve hundred men on the payroll whose average wage

was from ninety cents to one dollar and ten cents for a twelve-hour day. The mining

company owned all the houses in the town except three churches and two parochial schools

which were built from subscriptions from their members. The employees had to buy all of

their necessities from the Company store and money was little used since a sort of receipt

in script was all that was necessary to transact business. The Company erected a large

hotel which housed the officials.

When Iron Mountain was first discovered, or started, the mining was done

near the surface and securing the ore was a simple matter, but after a time this surface

ore became exhausted and more labor was necessary to extract it from the earth. The

company then gradually ceased to operate on a large scale.

For some years, beginning in 1859, Iron Mountain and Pilot Knob were the

southern terminals of the St. Louis and Iron Mountain railroad.

Published in a BRIEF AUTHENTIC HISTORY OF ST. FRANCOIS COUNTY,

MISSOURI. Compiled by J. Tom Miles, A.M. and published in The Farmington News in Ten

Chapters September 13 to November 15, 1935. Printed in booklet form through the courtesy

of J. Clyde Akers, County Superintendent of Schools.

HOIST HOUSE AT IRON MOUNTAIN BURNED

TUESDAY MORNING

Published by the LEAD BELT NEWS, Flat River, St. Francois Co. MO,

Fri. Sept. 21, 1923.

A fire, caused by the explosion of a gasoline torch in the hoist

house of the Iron Mountain Mining Co., at Iron Mountain early Tuesday morning, destroyed

considerable property and endangered the lives of a number of men who were in the employ

of the company.

The fire originated about 1 o'clock in the morning. Joe Oatman, hoist

engineer, was on shift at the time and describes the accident. Up to the present, electric

lights had not been installed in the hoist house. A gasoline torch had been used to

furnish light.

This torch exploded without a moment's warning, the flames filling the

entire room immediately. Oatman had a narrow escape.

The hoist house and hoisting tower were burned. Heavy timbers, ablaze,

fell into the shaft. Twenty men, who were at work in the mine at the time, made their

escape through a new tunnel that had been completed a few days previous to the fire. |